Money laundering: focus of conduct supervision (2019)

According to the Risk Monitor published for the first time in December 2019, money laundering remains one of the principal risks for FINMA’s supervised institutions and the Swiss financial centre. Shrinking margins can cause financial institutions to pursue risky business relationships. The financial flows associated with corruption and embezzlement can involve not just affluent private clients, some of whom must be treated as politically exposed persons, but also state or quasi-state organisations and sovereign wealth funds. The complexity of the structures involved, particularly when domiciliary companies are used, can increase the risk of money laundering. This is in spite of the fact that many institutions have further improved their money laundering prevention in recent years, are increasingly identifying suspicious assets and reporting them to the Money Laundering Reporting Office Switzerland (MROS).

Risk-based money laundering supervision

FINMA has analysed enforcement cases from recent years that focused on compliance with provisions for combating money laundering. The aim was to learn lessons that can be applied to regular money laundering supervision activities.

For each AMLA enforcement case, FINMA examined two key issues: firstly, why the serious breach of the Anti-Money Laundering Act was able to occur at the supervised institution in the first place and, secondly, how the chances of discovering the breach at an earlier stage as part of the regulatory audit could have been increased.

Features of past enforcement cases concerning the Anti-Money Laundering Act

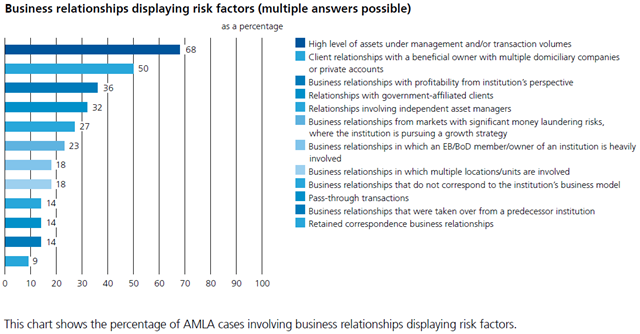

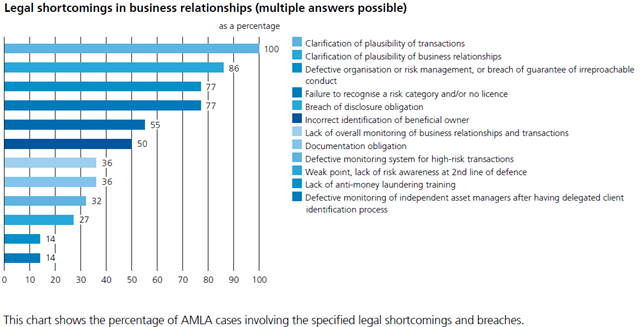

It transpired that many of the business relationships involved shared similar features, for example, very high asset values and transaction volumes, or business relationships involving beneficial owners with multiple domiciliary companies or high levels of profitability. There was also a pattern to the legal violations identified, such as a failure to question the economic plausibility of transactions or to recognise the increased risk.

These findings are also relevant with regard to how regulatory audits are performed. They demonstrate the importance of a risk-based spot-check sample, which increases the probability of suspected critical business relationships actually being audited.

When reviewing transaction patterns, these should in each case be considered in relation to the purpose and background of the business relationship. It is almost impossible to review the plausibility of transactions in the absence of a dedicated KYC process. The analysis also showed which aspects could be covered even better by money laundering supervision activities, including the status of compliance within the institution or the overall monitoring of business relationships and transactions across the company or group.

These findings have been incorporated into the revision of audit requirements for audit firms. FINMA now stipulates potential criteria to be applied when selecting the client dossiers to be audited with regard to the risk-based definition of the spot-check sample.

These criteria include, for example, business relationships managed across multiple locations or entities (shared relationships), business relationships managed by client advisers with the highest revenues or bonuses, business relationships in high-risk markets where the institution is pursuing a growth strategy or business relationships with government-affiliated clients.

Revision of AMLA audit requirements

As part of its supervisory activities, FINMA also monitors the financial intermediaries subject to its supervision with regard to their compliance with anti-money laundering requirements and in this respect, carries out a number of on-site reviews each year (31 in 2019). In addition to its own reviews, FINMA’s supervisory activities also primarily rely on the audit firms, which extend its reach and work in line with its directives.

The AMLA survey form is used as the basis for carrying out AMLA audits.

The partially revised FINMA Circular 2013/3 “Auditing” came into force on 1 January 2019. Aside from the applicable statutory provisions, it forms the basis for regulatory audits. The revision aims to increase the efficiency and effectiveness of audits by introducing multi-year audit cycles and a consistent risk orientation process. In light of these changes, it was the ideal time to revise the existing AMLA survey form.

Previously, the survey form comprehensively covered all AMLA obligations. Furthermore, it was the same for all institutions, leaving no latitude to be applied proportionally. Formal AMLA obligations were given as much weighting as material obligations. Following the revision of the survey form, AMLA audits will now be based more strongly on the risks involved. The audit items have been reduced to a sensible minimum, which have to be audited as part of every audit.

There are now also five thematic modules, which are applied in line with the risks involved. These relate to the monitoring of foreign booking centres, identification rules, complex structures, trade finance and a more in-depth focus on the topic of politically exposed persons.

Findings and focus of SRO supervision

Suitable structures, sufficient human resources and independent control functions are the key elements of an efficient, sustainable and internationally credible supervisory approach. This was mentioned back in 1996 in the dispatch on the Anti-Money Laundering Act (BBI 1996 III 1146).

In light of this, FINMA determined that the on-site reviews for self-regulatory organisations (SROs) in 2018 would focus on the quantitative and qualitative structuring of the SROs’ resources across their licensing, acceptance, supervisory and sanction processes.

As part of a benchmarking exercise, FINMA performed a cross-comparison of SROs to determine how their resources were both structured and allocated.

FINMA held an information event in summer 2019, where it presented its findings to recognised SROs. These showed that resources must be deployed more heavily in line with the risks faced. Furthermore, some SROs which had dedicated significantly fewer resources to supervisory activities than others, even though their members did not present a lesser risk, had to implement measures with regard to how their specialist resources are structured and allocated.

FINMA also determined that there is scope for improvement of SROs’ supervisory approach to material audits of breaches of their members’ due diligence obligations in accordance with Art. 6 AMLA and the associated review of violations of the disclosure obligation.

In 2019, FINMA determined that SRO supervision should focus on ensuring the independence of SROs as well as on how they deal with conflicts of interest.

This is a key requirement for putting in place a credible system of SRO supervision. As such, in 2019 FINMA’s on-site reviews included looking at whether independent supervision by the SRO can be ensured at all times, whether and which provisions are in place at the SRO to prevent conflicts of interest as well as whether recusal rules are being correctly and transparently followed. FINMA will notify the SROs of the findings of its consolidated evaluations of the key areas of supervision and of any actions that need to be taken.

Supervision of DSFIs comes to an end

Following the entry into force of FinIA/FinSA on 1 January 2020, FINMA’s supervision of DSFIs ended as of 31 December 2019, with any remaining DSFIs at the end of this period automatically being removed from DSFI supervision. DSFIs that continue to offer professional financial intermediary services as described under Art. 2 para. 3 AMLA after being removed from FINMA’s supervision must newly affiliate themselves with a recognised SRO by no later than the end of 2020.

(From the Annual Report 2019)